4 Elements of a Great Serverless Application Deployment Strategy

Serverless is the new Buzz word in town, selling developers the ability to focus on writing applications instead of managing servers.

This is true for the most part, but Serverless apps also have a certain property that can make their deployment and maintenance time consuming. That is, they depend on services - lots of them. A serverless architecture is typically designed over services for storing data, load balancing, data caching and code execution, just to name a few.

With that said, how do you both provision infrastructure and deploy code to test/staging/production environments in an automated and risk-minimized way?

If you can’t answer this question easily, or some part of your deploys still require you to look at your cloud provider’s console, then this post is for you.

Separate Environments Properly

To lessen the risk of integrating new code, most teams setup various environments to test the robustness of submitted code before it is pushed to production.

When configuring serverless architectures in these environments, special care needs to be taken in deciding whether a single stack or multi-stack approach architecture is best for your project. Otherwise, you might be wasting a lot of time on deployments, or even worse, introducing unnecessary risk to your application.

The single stack approach shares its services and infrastructure across all environments (like test, staging and prod). To differentiate between environments at runtime, environment variables or similar mechanisms are used.

In the context of a serverless app deployed on AWS, a single stack setup might configure a single Lambda Function with multiple aliases, an API Gateway with multiple stages, and a DynamoDB service with multiple tables - all with the purpose of supporting multiple test, staging and production environments.

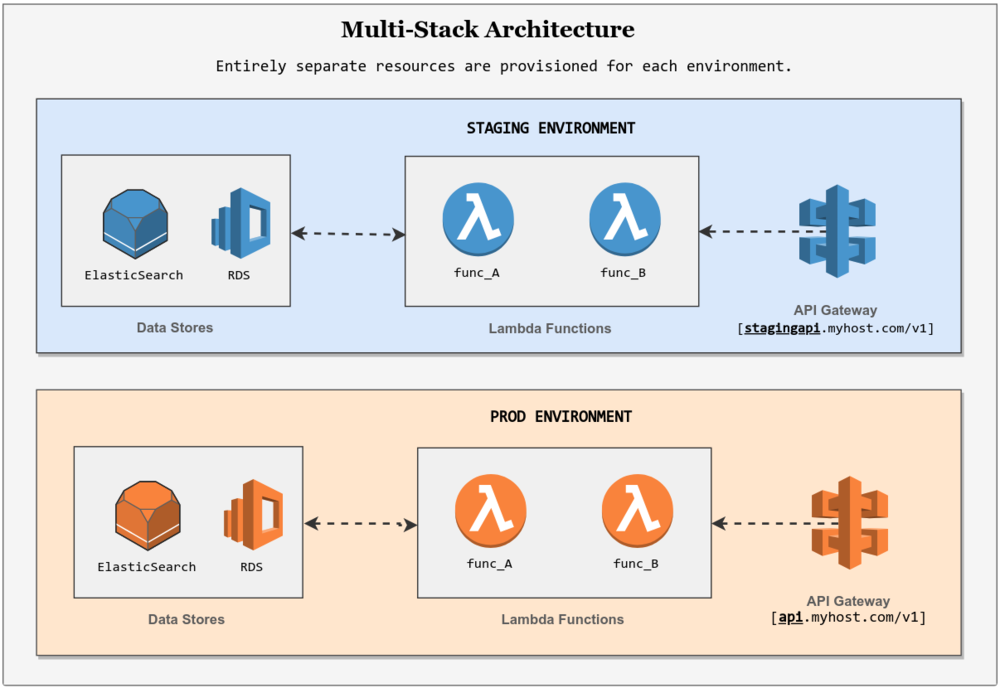

In contrast, a multi-stack approach uses a separate instance of each service for every environment and does not use API stages or Lambda aliases to differentiate between them.

Using the AWS example again, a multi-stack setup would configure a separate Lambda Function, API Gateway, and DynamoDB instance for each environment. If something goes wrong in a single stack approach, there is a greater chance that your production systems are negatively impacted as well. After all, the environments in this approach are provisioned on top of each other, and rely only on environment variables and lambda aliases for indirection.

In the multi-stack approach, this probability is decreased as a result of using separate resources for each environment. This advantage comes at a cost however - multi-stack approaches require more work to configure and maintain in comparison to single stack architectures. And in most scenarios, they are more expensive to run as well.

If you are in the early stages of your project, it might be a better idea for you to run with a single stack approach. Otherwise, a multi-stack approach is the way to go.

Continuous Delivery

The main idea behind Continuous delivery is to produce production ready artifacts from your code base frequently in an automated fashion. It ensures that code can be rapidly and safely deployed to production by delivering every change to a production-like environment and that any business applications and services function as expected through rigorous automated testing.

The most important point however, is that all of this must be automated.

Using their front end web application, Cloud providers such as Amazon Web Services make it easy to spin off a new lambda function for testing purposes or to update a function’s application code. However, all aspects of your continuous delivery strategy should be automated - the only manual step should be the push of the deploy to production button. This is vital for many reasons:

Minimizing Risk - Even with proper resource access controls in place which is seldom the case, the risk of accidentally causing bad things to happen are higher than you think. You definitely don’t want be the reason for a disruption to your service.

Scalability - As the number of developers in the project grows, and by extension, the volume of code deliveries, any process that is not completely automated will likely slow down your team’s agility.

Traceability - When your continuous delivery strategy is an automated, often using an automated pipeline of some sort, the use of deployments, builds and other components are better documented, making it easier to resolve and recover from failures.

Using Bitbucket pipelines, I usually use the following skeleton pipeline in multi-environment, continuous delivery environments. First, it runs your static analysis tools and automated tests for every Pull Request. Once the changes are deployed to master, it automatically updates the STAGING environment. Finally, the PROD environment is updated once the changes in STAGING are known to be safe using a manual trigger. If you are using AWS, checkout this repo for more information on the actual automated deployment of Lambda functions.

pipelines:

default:

- step:

name: Run Static Analysis Tools

script:

...

- step:

name: Run Automated Tests

script:

...

branches:

master:

- step:

name: Run Static Analysis Tools

script:

...

- step:

name: Run Automated Tests

script:

...

- step:

name: Update STAGING

deployment: staging

script:

(deploy to staging)...

- step:

name: Update PROD

deployment: production

trigger: manual

script:

(deploy to production)...App Config is Stored in The Environment

An app’s config consists of everything that is likely to vary between deploys (staging, production, developer environments, etc). This typically includes:

Resource handles to the database, cache or any other attached resources

Credentials to external services such as Amazon S3 or Twitter

Per-deploy values such as the canonical hostname for the deploy

Apps sometimes store config variables as constants in source code which is problematic for several reasons. First, any security sensitive related config data is visible to everyone who has access to the source code, which poses a serious security concern.

Additionally, config varies substantially across deploys, whereas code does not. Developing code that dynamically detects the environment and sets the appropriate config data as required results in code that is unnecessarily complicated and difficult to maintain, especially as the number of environments/deploys increases. On top of this, any required changes to an environment config requires pushing a change through the code base and waiting for it to propagate through the software delivery pipeline which is tedious and slow.

Rather than keeping your config data in source code, consider using consider using a service dedicated for this purpose like AWS Secrets Manager. Or as a slightly less safe but commonly used alternative, store this data in environment variables. Now your application can simply refer to abstract variables for config info, which are dynamically set by a build pipeline during deployment. In this way, environment variables can be leveraged to generate flexible and infinite variations (test, staging, prod, etc..) of your environment template. Lastly, environment variables are OS and language agnostic, which means they can easily be integrated across all types of projects.

Infrastructure is Provisioned and Deployed As Code

Infrastructure as Code (IaC) is all about provisioning and updating entire workloads (applications, infrastructure) using code. The idea here is that the same engineering discipline that is typically used for application code can be applied to deploying and managing workloads as well. You can implement your operations procedures as code and automate their execution by triggering them in response to events.

By using code to automate the process of setting up and configuring a virtual machine or container for example, you have a fast and repeatable method for replicating the process. So if you build a virtual environment for the development of an application, you can repeat the process of creating that VM simply by running the same code once you are ready to deploy.

Additionally, IaC processes increase agility. Developers don’t have to wait for however long the IT department needs to provision a new VM for them to do work.

When it comes to practicing IaC in the cloud, the Serverless Framework is a great tool for configuring serverless architectures. It’s a command line interface for building and deploying entire serverless applications through the use of configuration template files. It, along with many other services including AWS’s Serverless Application Model (SAM) for example, provide a scalable and systematic solution to many of the operational complexities of multi-environment serverless architectures. The Serverless Framework is probably the most popular cloud provider agnostic framework for configuring serverless applications and supports AWS, Microsoft Azure, Google Cloud Platform, IBM OpenWhisk, and more.

The typical serverless application uses a combination of cloud services, which often need to be configured and setup separately for each environment.

Serverless makes this process much more straight forward and scalable by utilizing a component based configuration where all the infrastructure and code for your entire application can be provisioned easily. Not only do these components conveniently refer to commonly used serverless services (AWS: S3 buckets, lambda functions, API Gateways, etc..), they can be re-used and composed into higher level components to build entire serverless applications. Components are open source, and there is lots of pre-built functionality developers can tap into right away.

As mentioned in the previous section, an automated continuous delivery solution is key for your serverless application. Serverless frameworks can be easily integrated into CI/CD pipeline to deploy sophisticated serverless applications in one step, making it much easier to manage multi-environment configurations.

Closing

Serverless applications often consist of plucking and combining various services and packages together which can make keeping track of everything a complex process, especially when running multi-environment setups.

In such scenarios, I feel it’s important that processes surrounding Serverless architectures should be scalable, automated, and require little manual intervention. This list represents my thoughts on how to deal with the complexity.